The museum was started more than fifty years ago and now houses some 535,000 ethnographic and archaeological objects, many of which originate from the Northwest Coast of British Columbia. It is Canada’s largest teaching museum and its collections, exhibitions and programs are renowned for giving access and insight into the cultures of indigenous peoples around the world.

When we arrived at the information desk we were informed that there was a tour starting immediately so we quickly joined it and took advantage of an excellent presentation by a well informed staff member. We were treated to glimpse inside the rich history of Canada’s First Peoples as told through their woodcarvings. In addition to the long term exhibits we also got a chance to view the visiting ‘Treasures of the Tsimshian from the Dundas Collection’ which included 48 pieces collected by Rev. Robert J. Dundas at Metlakatla, BC, in 1863.

When you first arrive at the museum you are greeted at the top of the stairs by two carved figures. One, carved by Musqueam artist Susan Point in 1997, is an Ancestor Figure holding a fisher (an animal believed to have healing powers); the other is a Welcome Figure by Nuu-chah-nulth artist Joe David, carved in 1984 to protest logging on Meares Island. Both figures are made of red cedar.

The large carved doors framing the entrance to the Museum were made in 1976 by four master Gitxsan artists: Walter Harris, Earl Muldoe, Vernon Stephens, and Art Sterritt. Represented on the doors is a narrative of the first people of the Skeena River region in B.C.

As you enter the Great Hall there are large scale sculptures from Coast Salish communities that are located on both sides of a ramp that decends into the main area. Further down and to your right you will find Kwakwaka’wakw carvings. Facing them on the left side are works from northern groups, including the Haida, Gitxsan (Tsimshian), and Nisga’a (Tsimshian).

Many of the large sculptures on the ramp were once parts of the cedar plank houses in which First Nations families lived. Some of the carvings served as posts supporting roof beams, while others were decorative. Coastal house carvings usually represent ancestors or powerful beings associated with the history of the residents of the house.

In the Great Hall you will find magnificent examples of works in red cedar originating from several communities, including the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, Gitxsan, Nisga’a, Haisla, Oweekeno, and others. These works include a number of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Totem poles which were removed from their original village sites in the 1950’s. With their owners’ cooperation, the pieces were selected, purchased, and moved to museums where they are now protected from decay and vandalism, and available for study by contemporary artists and researchers. Several of the larger poles were cut into smaller sections to facilitate removal. In some cases, First Nations artists made replicas of the poles which were returned to replace the originals.

The design of the Great Hall itself was inspired by the post-and-beam architecture of the First Peoples of the Northwest Coast of British Columbia.

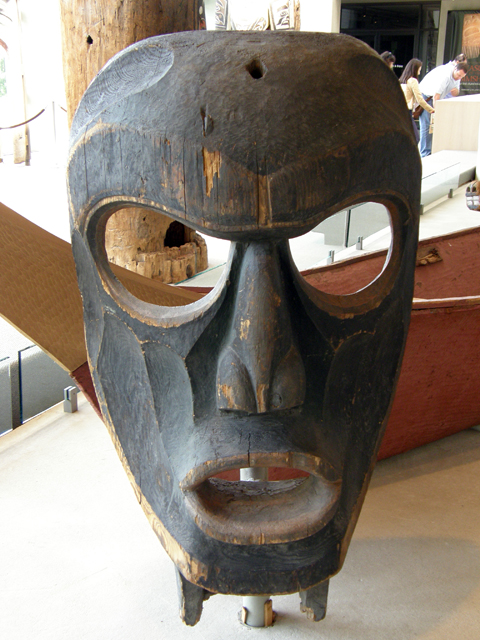

Here are some photos of the various artifacts:

The museum also houses the Rotunda which features Bill Reid’s acclaimed sculpture, The Raven and the First Men. This sculpture depicts a moment in the ancestral past of the Haida people when Raven, the wise and powerful yet mischievous trickster, has just found the first humans in a clam shell on the beach, and is coaxing them out of it:

Over the years we had seen many photos and read several articles of this sculpture so seeing it first-hand was a great thrill. We walked around it several times, something that is hard to do with photos. We hope we are able to give a good 360 degree view above.

Outside of the museum is the Haida House complex which includes structures that would have been present in a nineteenth century Haida village. Constructed in 1962, this complex includes a large family dwelling and a smaller mortuary house similar to those used traditionally to hold the dead.

In front of the houses are examples of memorial and mortuary poles dating from 1951 to the present. Haida artist Bill Reid and ‘Namgis artist Doug Cranmer oversaw the construction of the houses, and carved several of the adjacent poles. Other poles on display were carved by Jim Hart (Haida), Chief Walter and Rodney Harris (Gitxsan), and Mungo Martin (Kwakwaka’wakw). Framing the path to the complex are two massive houseboards carved by Musqueam artist Susan Point in 1997.

Although the museum experienced a break-in only days earlier where 15 pieces of Bill Reid and Mexican gold art were stolen it was business as usual on the day of my visit. The only tell tale sign of this unfortunate incident was a display that was blocked off. At the time of writing 13 of the 15 pieces had been recovered.

Whether you are a woodcarver, a history buff, someone with in an interest in Pacific North Coast art or just someone who wants to spend a great couple of hours, adding MOA to your visit list when in Vancouver is certainly worthwhile.

You can find more information on the MOA here.

Back to the shop…